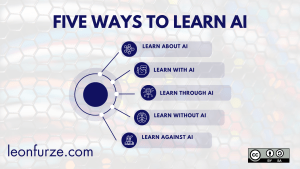

About, With, Through, Without, Against: Five Ways to Learn AI

I’ve worked with generative artificial intelligence in education for a few years now, and like any novel technology, it’s come with equal parts hype and threat. In just the past few months, we’ve seen articles celebrating the potential of AI to accelerate learning, while at the same time turning students’ brains into soup and rendering otherwise capable students somehow unable to learn.

It doesn’t take a degree in cognitive science to know that both of these extremes devalue learning and are frankly insulting to young people. Technologies do make things more “efficient“. Technologies also lead to skills loss, but young people are adaptable, competent, curious and capable, and we need more nuanced discussions than unhelpful binaries over whether AI helps or harms learning.

In this post, I’m going to outline five ways to view learning and artificial intelligence. These aren’t the only five ways. Some of them overlap, and I’m sure you can think of different ideas, and that’s exactly the point. There is no one answer to any of these problems. There is no one right approach to learning, with or without artificial intelligence.

Learning About AI

This is what some people at the simplest level might call “AI literacy”. I’m not a huge fan of that term, since I think that, like other forms of literacy, it will end up being reductive and turn into a series of standardised tests, which then generally become benchmarks to beat teachers and students with. Think PISA, or if you’re in Australia, NAPLAN.

AI literacy is generally concerned with teaching students how to use technologies, but sometimes misses out on why and when. Learning about AI could include engaging with technologies as a consumer, such as how to prompt a text-based model, how to use image generators and so on, or it could go a step further upstream and look at how artificial intelligence models are constructed, such as teaching about algorithms, data or the architecture of large language models.

Learning about AI is an important skill given the growing ubiquity (note, I didn’t say inevitability) of these technologies. But learning about AI is not necessarily the job of the disciplinary teacher. It is not the job of the English teacher to teach students how to use ChatGPT. It is not the job of the maths teacher to arbitrarily teach concepts related to machine learning if they fall outside of their standard agreed upon curriculum.

What I don’t want is to see schools, universities or sectors adopting terms like “we are all teachers of AI literacy.” We’ve seen how that’s turned out for regular, old-fashioned literacy. It doesn’t end well, and it’s not true. We’re not all teachers of AI literacy. I’m an English teacher. Primarily, I want to teach students how to read and appreciate literature, not how to use the best prompt in ChatGPT or anything else.

I do believe that there are places within subject disciplines, though, to teach aspects of AI, and I’ll talk about those in the other sections in more detail. For learning about AI, I believe the best vehicle is in extracurricular AI literacy modules, self-guided learning, and delivery through computer sciences or subjects where artificial intelligence is already a core part of the discipline. For learning how to prompt ChatGPT, students can probably do that on TikTok.

But the role of educators should expand beyond AI literacy to helping students understand why and why not to use AI.

Learning With AI

Learning with AI might encompass the types of learning favoured by technology companies, tutor chatbots, AI learning assistants, ChatGPT’s new study mode, or Google’s new “guided learning”. This is platforms like Khanmigo from Khan Academy, which have been designed specifically to support learning without offloading the answering of the questions.

Honestly, I think personalised learning with AI is largely a myth. I think chatbots in education are still a dead end and not a particularly useful user interface for interacting with a large language model based technology. But I do believe that there are ways to learn with AI. I regularly use platforms like ChatGPT and Claude myself when I’m dealing with unfamiliar concepts that I know these models are good at; for example, when developing code blocks for my website, or writing automations with Python. Although ChatGPT and Claude don’t “know” anything, per se, they have trained on a large corpus of information, which means that they are much better at writing HTML code than I am. But I wouldn’t try to learn a foreign language with ChatGPT.

In subject disciplines, learning with AI might look like a custom chatbot designed and deployed by a teacher with a particular subject discipline in mind. This is the approach taken by University of Sydney’s Cogniti, for example, which encourages educators to upload course documents to create custom chatbots specific to particular units of work. Learning with AI, in this sense, takes on something of an administrative turn. A chatbot might help a student navigate curriculum materials, understand the course syllabus, or perhaps sense check and reflect on things that they’ve already learned.

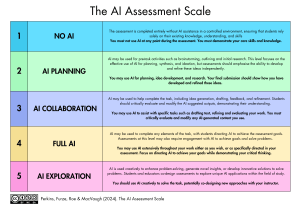

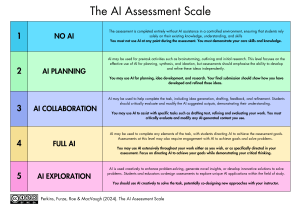

Learning with AI might also look like level three of our AI assessment scale, where we encourage and explore the use of artificial intelligence for drafting work and getting feedback. For example, a student might upload a criteria sheet and a sample of their work and invite a chatbot to give feedback. This could be part of a self-assessment process, or could augment a teacher’s assessment and feedback. Learning with AI leverages the “chattiness” of chatbots, and engages a large language model in a dialogue to further a learning activity.

Learning Through AI

Having said that chatbots are a dead end in education and that I don’t really believe that personalised tutors will be replacing teachers anytime soon, there are ways that large language models and other AI-based technologies can support learning. Rather than treating AI as a “collaborative partner”, learning through AI means using artificial intelligence and AI-based applications as a conduit or medium.

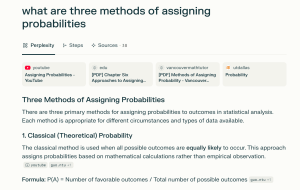

For example, many search engines like Google and Perplexity, as well as certain academic applications like Elicit for literature reviews, use large language models to conduct semantic search, taking a user’s query and synthesising results through the large language model in a way which is not possible with a traditional search engine. Learning through AI might also involve using other kinds of artificial intelligence, data analytics and so on, to augment a learning experience.

As generative AI matures as a technology, I believe that learning through AI will become more common, and the technologies will become baked in to many of our everyday technologies, such that they recede into the woodwork and we don’t actually realise that we’re using them. Of course, as I’ve written before, there’s a corporate imperative to make AI technologies disappear, and I think we’re already starting to see that. There’s been a toning down in recent years of the magical and mythological language of artificial intelligence and a shift towards integrating them in much more mundane ways, into word processors, PowerPoint software and so on.

In subject disciplines, learning through AI means using the best available technology, when and where it’s appropriate to meet the learning outcome. If that happens to intersect with artificial intelligence, so be it. If not, there’s no need to force it.

Learning Without AI

This one is pretty self-explanatory, but there appear to be some commentators online who think that AI Special Sauce needs to be poured all over everything for it to be successful. This includes the growing numbers of people concerned that if we don’t teach artificial intelligence in every subject at every level of schooling, our students will somehow be left behind.

Let’s be really clear: students learned before AI, they are still learning during this disruptive period of time, and they will continue to learn after ChatGPT has been and gone, and we’re left with the remnants of whatever the technology looks like after this bubble bursts. Literature will still be literature; history, history; the arts, the arts. Students will still need to know how to understand mathematical concepts, with and without technologies. Research skills will still be important, even when products like Deep Research can conduct increasingly competent reports. Computer programming skills, the decomposition of complex tasks, and the fundamentals of programming will still be important, even when artificial intelligence becomes more proficient than a human coder across all known programming languages.

In short, learning without AI is, and will always be, important.

Learning Against AI

Not only is learning without AI important, it is vital that students understand why they should actively work against AI. In some cases, learning against AI encompasses some of the more critical aspects often neglected by AI literacy. If you wanted to simplify, it could perhaps even be placed at the opposite end of the spectrum to learning about AI, though it might be more accurate to suggest that the two things overlap. You have to have both the technical understanding and the critical awareness. You have to know how the technology works and why it is inherently problematic. Without those understandings, for a start, the technology will never improve. Biased technology will remain biased. Environmentally unsustainable practices will continue to put the climate at risk.

Learning against AI also includes methods which might be described as actively disruptive, such as how to circumvent or at least navigate the increased data collection, surveillance and algorithmic profiling of our day to day lives online. Learning against AI is a thoughtful, critical, political and absolutely necessary act, and one which is entirely the role of education. If education stops at learning about AI or descends into a chatbot tutor-fuelled parody of learning with AI, then we’re doing a disservice to our students. We’re teaching them how to be good consumers of technologies like ChatGPT until whatever the replacement for ChatGPT is emerges.

So, learning against AI brings us full circle. Learning against AI is also perfect for being taught through the disciplines. Deepfakes, misinformation and the political use of artificial intelligence is great material for the English classroom. Examining what can go wrong through speculative and dystopian literature is a necessary precursor to discussions about what can go right. Both mathematics and sciences offer perfect opportunities for exploring algorithmic discrimination, but this is also something that can also be discussed in healthcare classes.

In fact, I think learning against AI is much more interesting than learning about AI in the subject disciplines. As an English teacher, I don’t want to teach students five ways to improve ChatGPT prompts for better persuasive blog posts. I want to analyse the language used by different large language models to interrogate their obscure and deliberately opaque training methods. As a maths teacher, I wouldn’t want to spend too much time exploring how more capable models like Google Gemini Pro 2.5 Advanced Mega Ultra 9 Premium are great at mathematical reasoning and complex tasks. I want to apply my students’ understanding of algorithms to give them insight into why, despite all of the hype and mythical thinking, large language models are essentially just sophisticated predictive text. In the visual arts, I might spend a little bit of time exploring image generation and looking at it as a contemporary way of producing digital media, but I think I’d find it much more interesting to look at a case study of why these companies are being sued by countless artists around the world for the abuse of their intellectual and creative properties.

These are meaningful issues worth talking about with students, young and old.

Conclusion

Here I’ve outlined five ways to learn with and without artificial intelligence. The key is balance, nuance, not an outright rejection or refusal and nor a starry-eyed embrace of the technology.

I’d love to hear from you if you have ideas about ways to learn with and against AI that I’ve missed, if you’ve got examples from within your own areas of expertise. Get in touch via the form below or drop a comment wherever you found this article.

Post-script

A few days after posting the article, Peter Holmboe messaged me on LinkedIn to say he’d read something very similar before.

Joscha Falck’s Lernen und Künstliche Intelligenz has five dimensions: Despite, With, About, Through, Without. And from what I can see it was published way back in 2023!

It’s not exactly the same, but it’s pretty damn close. Peter’s message has me wondering if I absorbed Joscha Falck’s article by osmosis at some point (despite not being able to read German…), but whether I did or did not it’s well worth a read and worthy of attribution.

Falck’s original materials are CC BY SA 4.0 so I have added the open licensing to mine, and shared his original article here and on the socials.

Check out Falck’s article here: https://joschafalck.de/lernen-und-ki/

Want to learn more about GenAI professional development and advisory services, or just have questions or comments? Get in touch:

Read More

Stay up to date with the latest from the blog.

How (not) to use the AIAS

Digital Plastic as a framework for Critical AI Literacy

What Do Educators Want to Learn About GenAI?

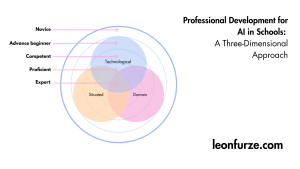

Professional Development for AI in Schools: A Three-Dimensional Approach

Using Metaphors to Teach Critical AI Literacy

Artificial Intelligence in Vocational Education

Flash Fic Friday: Volume 1

Five Principles for Rethinking Assessment with Gen AI

About, With, Through, Without, Against: Five Ways to Learn AI

Open Source AI is Going Mainstream

The post About, With, Through, Without, Against: Five Ways to Learn AI appeared first on Leon Furze.